Sanatan Articles

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

JOIN SATYAAGRAH SOCIAL MEDIA

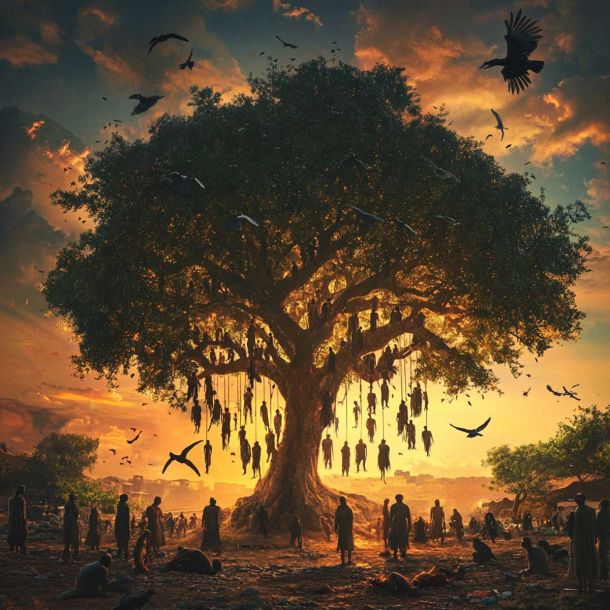

On 8 June 1980, in a forgotten chapter never taught in textbooks, over 350 Bengali Hindus were butchered and 2 lakh displaced in Mandai massacre—India’s own 'My Lai'—where flames, daos, and silence erased an entire community from history and memory

The quiet morning of 8th June 1980 in Mandai, a small village in Tripura, turned into a day of bloodshed that would scar the history of independent India forever. In what has come to be known as the Mandai massacre, hundreds of Hindu Bengali refugees—men, women, and children—were slaughtered in cold blood by armed tribal mobs in a pre-planned assault that shook the entire nation.

|

What unfolded on that day was a massacre so horrifying that even military officers compared it to the infamous My Lai massacre of 1968 in Vietnam. An estimated 350 to 400 Bengali Hindus were killed in a single day, turning Mandai into a mass graveyard and making the episode one of the worst ethno-religious atrocities in the post-independence era.

Just 30 km away from Agartala, the capital of Tripura, the village of Mandai had long been home to both the indigenous tribal people and a minority of Bengali Hindus, who had settled in the area for over two decades. These Bengali Hindus were not recent migrants; they were refugees from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) who had fled previous religious persecution.

However, the demographic shift caused by the influx of these refugees, especially after the 1971 India-Pakistan War, ignited longstanding tensions between the tribal communities and the Bengali settlers. This resentment was politically weaponized during the 1970s, particularly by the Tripura Upajati Juba Samiti (TUJS)—a tribal political party that thrived on anti-Bengali sentiment.

This tension didn’t remain confined to politics. Several armed extremist outfits like the Tripura National Volunteers (TNV) and Sangkrak Army (also called “The Mighty One”) began to exploit the volatile environment. They built an atmosphere of fear and hostility that paved the way for what was about to happen.

The tipping point came from a minor but significant incident. In the Lembucherra Bazar, a group of shopkeepers, believed to be Bengalis, had reportedly assaulted a tribal boy. This incident, whether accidental or deliberate, sparked a large-scale tribal retaliation. A mob of more than 1,000 tribals descended on the market, vandalizing shops and killing people. The bazar was shut down for a week, and the TUJS used the incident to rally even more tribal support, stoking hatred.

Meanwhile, the Sangkrak Army, with arms allegedly sourced from the Mizo National Front (MNF), seized the opportunity to strike markets in Thelakung and Gulirai, both situated roughly 30 km from Mandai. These coordinated acts of violence were not random but part of an orchestrated plan leading up to the mass killings in Mandai.

On 8th June, the worst fears of the Bengali Hindus came true. Around 1,000 armed tribal extremists, carrying guns, spears, swords, bows, arrows, and daos (scythes), launched a surprise attack on Mandai. Their first demand was not blood but money. The terrified villagers handed over around $250, the only cash they had. But it was not enough to spare their lives.

The victims were gathered at the market square, their homes set ablaze in front of them. And then began the mass slaughter. As described by Time Magazine, “In the worst massacre, in the village of Mandai, the tribals first demanded money, then corralled the Bengalis in the village market. The horrified settlers were forced to watch while tribesmen armed with guns, spears and heavy scythes called daos put the torch to dwellings and butchered their occupants.”

The world soon caught wind of this brutality. A Pittsburgh Post-Gazette headline from June 16, 1980, screamed: “350 Bengalis Are Massacred in Indian Village.” The report confirmed how once the Bengali villagers were cornered, the killers began their onslaught with terrifying cruelty, using daos and rifles.

Survivors described the scenes of carnage with trembling voices. “There was blood everywhere,” some recalled, describing how their loved ones were hacked to death. The Indian Army, which reached Mandai a day later, discovered at least 350 mutilated bodies. Many had crushed skulls or severed limbs. Children were stabbed, bodies were cut in half, and several decomposing corpses were later found floating in nearby rivers.

One of the most horrific discoveries was that of a six-month-old infant, whose body was dumped in pieces on either side of his mother’s corpse.

The Army had to bury the bodies in shallow graves, often in makeshift pits. Mandai was now a village of ashes—burnt homes, broken pots, charred walls, and bloodied sewing machines were all that remained. No police came to help, as the nearest outpost was 7 miles away in Jirania and could not respond in time.

An eyewitness, former Mandai MLA Manoranjan Debbarma, recounted, “Children were spiked to death and wombs of pregnant women were ripped open. We had lived through a horrific, difficult time.” While the official death toll stood at 255, military sources claimed over 700 people were killed.

The violence did not end at Mandai. It spread like wildfire to other districts of Tripura, with continued arson attacks and killings. The overall death toll from the series of attacks is believed to range between 2,000 and 10,000. An estimated 1.5 to 2 lakh Bengali Hindus were displaced and forced to live in refugee camps.

By June 9, Indian authorities scrambled to respond. According to reports, 5,000 security personnel, including 1,000 Army soldiers, were deployed across western Tripura to contain the violence. Relief operations were activated quickly, as roughly 243,000 displaced persons, mostly Bengali Hindus, sought refuge in temporary shelters by mid-June.

Major R. Rajamani, who led the Army unit that entered Mandai, shared his chilling experience with The New York Times. “I have heard of My Lai. I wonder whether that was half as gruesome as here.” He added, “That first day, I saw a six-month-old child chopped into two with each piece lying on either side of his dead mother. I have never seen anything like it, nor do I want to.”

A UNI reporter who reached the scene observed, “There were shallow graves from one of which a hand was visible.” The Inspector General of Police at the time, Satyabrata Basu, made a bold statement, calling the Mandai massacre an act of ‘genocide.’

|

Bengali Hindu Victims Narrate Their Ordeal

The horror of the 1980 Mandai massacre is not just measured by the death toll, but by the unimaginable pain and haunting memories left behind for those who survived. Every survivor became a living witness to a tragedy that the rest of the country quickly forgot. Their stories reveal the raw human cost of hatred that spilled over into blood-soaked vengeance.

One such survivor was Haradhem Seal, a 20-year-old Bengali barber. He was not just a victim, but a man who saw his entire world shattered in just a few hours. He lost his parents, three sisters, and three brothers in the horrifying bloodbath. In an interview with Time Magazine, he recalled: “There was blood everywhere. One man hacked at me with his dao. I collapsed, then several bodies fell on top of me. That was probably what saved me.” His survival was nothing short of a miracle—buried under corpses, lying still while the bloodthirsty mob assumed he was already dead.

The pain was equally unbearable for Subarna Prabha Deb, another survivor who recounted the loss of her two daughters and a grandchild, all hacked to death in Mandai. Her son was left seriously injured, carrying physical and emotional scars that would last a lifetime. Like many mothers, she could only watch helplessly as her family was destroyed in front of her eyes.

Then there was Abani Dey, a 65-year-old man who had already survived one wave of ethnic violence. Years ago, he had lost his parents and sister to Muslim mobs in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). He and his family had hoped Tripura would offer them the peace and dignity they never found across the border. But that hope too was crushed. In an emotional statement to the media, he said, “When we came, the tribals here welcomed us and helped us to settle down. We thought we had found a safe place. Now this. Where can we go?”

His grief deepened when he shared how his 15-year-old son was brutally killed in the attack. “A tribal caught his hair and chopped off his head with a scythe. We were watching it from a distance,” he lamented, the image of that moment forever etched in his memory.

Nagendra Saha, 45, was yet another Bengali Hindu who lived through that day of terror. He recounted how his two sons were murdered before his eyes. Describing the final moments, he said, “As the tribals came nearer we prayed aloud, ‘Oh God. Please save us.’ Once we were outside, they swung their daos at us. One man gave me a chop on my head and I fell unconscious. Before hitting me, I saw him force an old woman to lie on the ground and he smashed her head with the dao. My two sons died within seconds of one another,” he emphasised.

The massacre at Mandai didn’t end with the mass killings of Bengali Hindus. It unleashed a cycle of violence that soon spread across other parts of Tripura. In retaliation, there were attacks on tribal communities in Bengali-majority regions. Reports of arson and the forced migration of tribals started surfacing. According to records, more than 12 refugee camps were set up to house displaced tribal families.

One tribal victim, Suhed Deb Burman, summed up the collective despair of his people by stating, “We have become refugees in our own land.” His words captured a tragic irony—both tribals and Bengalis were caught in a storm that neither side fully understood nor controlled.

|

Political Reaction to the Mandai Massacre

In the immediate political aftermath, the then Chief Minister of Tripura, Nripen Chakravarty, did not mince his words. He acknowledged the nature of the killings with chilling honesty: “This looks like an absolutely pre-planned attack. They are on a killing spree… But no one could have anticipated this kind of massacre.” His words highlighted a sense of shock and helplessness at the scale of the violence that had unfolded.

Chakravarty also accused the Indira Gandhi-led Central Government of failing to act in time. He claimed that no army support had been sent despite growing signs of tribal unrest. Though there was some talk in political circles of dismissing the state government for its failure to maintain order, the Centre ultimately refrained from taking that step.

Still, the Union Government did respond. Home Minister Zail Singh personally visited Tripura to assess the crisis. The Centre arranged to send 5,000 tonnes of rice to support relief efforts and promised rehabilitation and resettlement for the victims. In the days that followed, refugee camps were established to shelter the displaced, offering at least temporary solace for thousands who had lost everything.

The Mandai massacre shook Tripura’s social foundations. Even decades later, it remains one of the darkest episodes of ethnic violence in the state’s history. Analysts, writers, and political historians have drawn parallels between Mandai, the My Lai massacre of Vietnam, and India’s own Nellie massacre in Assam, underscoring the scale and brutality that unfolded in just a few hours.

The event also reshaped the political discourse in the state. Discussions around land rights, tribal autonomy, and ethnic representation began to dominate the political agenda. Eventually, in 1985, the Tribal Areas Autonomous District Council was formed in Tripura to address long-standing tribal grievances and give them a voice in governance.

Yet, the memory of Mandai remains a sensitive subject in political campaigns. One veteran legislator who survived the massacre put it best when he said his community “lived through a horrific, difficult time”, even as he chose to focus on peace and development in his constituency. Mandai, he believed, was a reminder of how quickly communal harmony can be destroyed when ethnic conflict and land disputes are left unresolved.

The horror of Mandai has largely faded from national memory, but for those who survived it, the trauma remains fresh. This was not just a village massacre—it was a calculated act of mass murder, a dark stain on India’s history that must not be forgotten.

Changing Demographics of Tripura

The tragic events that unfolded in Mandai in 1980 were not an isolated incident. They were rooted in a deeper, decades-old story of migration, political shifts, and identity struggles that reshaped the very landscape of Tripura. The ethno-religious tensions that shook the region to its core had been brewing silently for generations, and the consequences were devastating.

Tripura, one of the smallest states in India, experienced a massive demographic transformation in the 20th century. At first, the Tripuri rulers themselves encouraged the settlement of Bengali Hindus, who were seen as contributors to administrative and educational development. However, the real demographic explosion began after two key geopolitical events: the Partition of India in 1947 and the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971. In both cases, waves of Bengali Hindu refugees fled East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) to escape persecution and communal violence, seeking safety in the Indian Northeast.

But this large-scale migration came at a cost. As Bengali Hindus settled across Tripura in huge numbers, the tribal population slowly started to shrink in proportion. By 1971, the tribals had become a minority in their own state, accounting for just 28.95% of the population. This shift led to increasing anxiety, resentment, and a sense of cultural alienation among the indigenous communities.

The situation grew worse in the 1980s when tensions reached a boiling point. The relationship between Bengali Hindus and tribal communities became strained—especially as Christian missionary activities among the tribals led to a new cultural and religious identity that sometimes stood in contrast to the Hindu refugee population. Conflicts, targeted violence, and massacres began to rise as extremist sentiments took hold in various groups.

While the Bengali Hindus had fled to Tripura to escape Muslim-led atrocities in East Pakistan, they were now finding themselves in conflict with the natives of their new homeland. The economic advantage they had in trade, services, and access to plains, coupled with their growing political influence, only deepened the tribal discontentment. This resentment became a breeding ground for tribal extremism, leading up to the Mandai massacre.

And Mandai wasn’t the end.

The 2000 Bagber massacre, where terrorists from the Christian Tripuri outfit National Liberation Front of Tripura (NLFT) opened fire and killed innocent Bengali Hindu refugees, was another grim reminder that ethnic hatred had not died out. Then came the 2002 Singicherra massacre, where 16 unarmed Bengali Hindus were ruthlessly killed, again exposing the ongoing fault lines of Tripura’s identity politics. Each of these attacks was brutal, and each added to the pain that communities were already struggling to heal from.

|

End of Tribal Extremism in Mandai and a Silver Lining

The scars of Mandai ran deep. The massacre had torn apart families, wiped out entire households, and burned a haunting image into the memory of both Bengali and tribal communities. For years after the massacre, Bengalis who had lived in Mandai fled the village, seeking refuge wherever they could find safety. For them, Mandai had turned from home to horror overnight.

In the aftermath, Mandai remained a center of tribal insurgency and extremist violence, with shadowy groups continuing to influence the region. This continued until at least 2009, nearly three decades after the massacre. But then, things slowly began to change.

A new chapter of hope began in 2015, when Mandai made headlines again—this time for a remarkable achievement in development, not destruction. In November 2015, it was reported that the Mandai block had outperformed over 6,800 blocks across India in areas of financial literacy and inclusion. The transformation was so significant that Prime Minister Narendra Modi himself awarded the Mandai block in a national event held in New Delhi.

This recognition marked a turning point for a region once associated with tragedy. Former District Magistrate of West Tripura, Abhishek Singh, proudly shared the progress: “Mandai block has achieved over 100 per cent target in providing access to banking and financial services and has become a role model for the others. As a result of financial inclusion, more and more tribal people of the block are now connected to banks for access to Government aid.”

This progress was more than just numbers on a report. It reflected a change in mindset, infrastructure, and opportunity—a symbol that even a place known for one of India's bloodiest massacres could rise above its past.

Today, the situation in Tripura is starkly different from the dark days of the 1980s. Ethno-religious conflicts have become rare, and the majority of tribal extremist outfits have surrendered, laying down arms and choosing peace. Both Bengali and tribal communities now share a common dream—to build a future that is stable, inclusive, and free from fear.

Tripura, as it stands today, is no longer defined by its bloodshed but by its resilience. The old scars may never fade, but they have not stopped the people from moving forward and rebuilding their lives. The memory of Mandai remains, but it no longer dictates the destiny of the state. Instead, Tripura is stepping into an era of growth and unity, determined never to look back in anger but only ahead in hope.

Support Us

Support Us

Satyagraha was born from the heart of our land, with an undying aim to unveil the true essence of Bharat. It seeks to illuminate the hidden tales of our valiant freedom fighters and the rich chronicles that haven't yet sung their complete melody in the mainstream.

While platforms like NDTV and 'The Wire' effortlessly garner funds under the banner of safeguarding democracy, we at Satyagraha walk a different path. Our strength and resonance come from you. In this journey to weave a stronger Bharat, every little contribution amplifies our voice. Let's come together, contribute as you can, and champion the true spirit of our nation.

|  |  |

| ICICI Bank of Satyaagrah | Razorpay Bank of Satyaagrah | PayPal Bank of Satyaagrah - For International Payments |

If all above doesn't work, then try the LINK below:

Please share the article on other platforms

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text. The website also frequently uses non-commercial images for representational purposes only in line with the article. We are not responsible for the authenticity of such images. If some images have a copyright issue, we request the person/entity to contact us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and we will take the necessary actions to resolve the issue.

Related Articles

- Violence Against Minority Hindus in Bangladesh: The Mistier World Of Silence

- 'Hinduon se Azadi', 'La ilaha illallah' and 'Ghazwa-e-Hind' slogans by Muslims was secular leading to Genocide of Kashmiri Pandit: Then and now, from Azadi slogans to Hindu hate, the nature of Jihad and its apologists remain unchanged

- Tipu Sultan remembered as killer of Brahmins and demolisher of temples in many villages of Tamil Nadu: a freedom fighter or Islamic bigot?

- Haunting history- 50 years of Operation Searchlight in Dhaka

- The true face of Saba Naqvi: How the ‘secular journalist’ supported Muslims acts of violence and fanaticism on Ram Sevaks in Sabarmati Express burning leading to gruesome killing of some 59 innocent people, including 25 women and 15 children

- “We are preaching hope, standing on the piles of bones of the past”: Fall in Bangladesh’s Hindu population confirms their genocide, total population of the country has more than doubled over 50 years, but that of Hindus has dropped by around 7.5 million

- The untold exodus of 1.5 lakh Punjabi Hindus to Delhi’s Piragarhi camp; forced upon by Sikh radical Khalistani terrorists led by Bhindranwale

- Lack of awareness among Hindus of it's Sanatan Culture is the root cause of Academic Hinduphobia: Demand for Hindu Rashtra is the need of the hour

- The first large-scale massacre in Independent India accounts for one of the biggest coverups in modern history: It is about time we talk about the 1948 genocide of Maharashtrian Brahmins following MK Gandhi’s assassination

- Winston Churchill's hate for Indians caused millions of deaths: A villainous supremacist

- Censor committee of Kerala denied certificate to upcoming Malayalam film ‘Puzha Muthal Puzha Vare’ by ex-Muslim filmmaker Ali Akbar aka Ramasimhan Aboobakker, film revolves around 1921 Malabar genocide of Hindus by Moplah Muslims

- Literary genius Charles Dickens though a gifted story-teller but in reality, was a genocidal racist and Christian fundamentalist who hated Hindus and wanted to exterminate this race from the face of the earth

- Hindus documented massacres for 1000s of years: Incomplete but indicative History of Attacks on India from 636 AD

- Why Hindu-Sikh genocide of Mirpur in 1947 ignored? Why inhuman crimes of Radical Islamists always hidden in India?

- "Dignity, not Disrespect: The Call for Justice": During Ganesh Chaturthi in Leicester, a harrowing episode unfolded as a police officer exhibited stark misconduct towards an elderly Hindu priest, igniting widespread outrage and calls for immediate action